I am fascinated by the Edwardian period and its clothing as a kind of final declaration of past decadence before the modern world. Underneath the old world aspects of the Edwardian period, however, is the emergence of modern attitudes and lifestyles. The fashion designer that I think best portrays this tension in the Edwardian period is Lucy Christiana, Lady Duff Gordon (13 June 1863 – 20 April 1935). Lucy was the founder of the fashion label Lucile Ltd. Her ancestors were thought to be descendants from the Scottish and French aristocracy, but this seems to have been very far back in their ancestry (almost wishful thinking) and her grandparents on both her mother’s and father’s side were essentially pioneers in the outback that Canada was until… well it still is a bit of an outback. At any rate, Lucy’s father Douglas Sutherland, though from rather humble beginnings, had become relatively well off working as an engineer. At the age of 28, however, Mr. Sutherland died in London and so her mother brought Lucy and her younger sister Elinor (17 October 1864 - 23 September 1943) to live at their grandmother's house in Guelph, Ontario, which is not far from where I live now in Toronto. At the age of nine Lucy's mother re-married a man by the name of Mr. Kennedy in order to move away from her controlling grandmother only to find herself married to a controlling man who had a penchant for drinking. When Lucy was nine, they moved back to England for a short time, until finally settling on the Island of Jersey, just off the coast of Normandy. Lucy began to sew clothing for herself, Elinor, and her mother because Mr. Kennedy was unwilling to dish out any large sum of money for their wardrobes.

Lucy is best known for her tea gowns, and in their design it is obvious that she was able to capture the decadence and frivolity of her time through the use of lace, chiffon and copious amounts of silk flowers. Though in this way, she epitomizes the Edwardian epoch, it is both her business and personal life that show how incredibly modern she was. She rashly married James Stuart Wallace in 1884, and the marriage quickly deteriorated. After five years of marriage Lucy decided to divorce her husband, which is perhaps the first full expression of Lucy as a modern woman. To say that divorce at this time was stigmatized is an incredible understatement. Not only that, but it was also very expensive, making it almost impossible for women to obtain a divorce. It was Lucy’s devoted mother, Mrs. Kennedy, who paid for the divorce with the money that her late husband had left her. This inheritance, which was greatly depreciated by the divorce, also paid for a small house in London for Mrs. Kennedy, Lucy and her daughter Esme. Cast out of polite society, Lucy was thrown into haute bohemia, where she decided to make clothes for a living, given that it was the only skill she had that could be potentially profitable. In her mother’s house, she began to make clothing for some friends, and for her sister. In a short five years, she had built a profitable and large business for herself as a couturier and by 1915 Lucy had houses in London, Paris, New York, and Chicago. She remarried in 1900 to Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, but never again would she live under the command of a man. Although Lucy and Cosmo stayed connected personally and through the business of Lucile Ltd, they lived separate lives for most of their marriage.

Lucy is best known for her tea gowns, and in their design it is obvious that she was able to capture the decadence and frivolity of her time through the use of lace, chiffon and copious amounts of silk flowers. Though in this way, she epitomizes the Edwardian epoch, it is both her business and personal life that show how incredibly modern she was. She rashly married James Stuart Wallace in 1884, and the marriage quickly deteriorated. After five years of marriage Lucy decided to divorce her husband, which is perhaps the first full expression of Lucy as a modern woman. To say that divorce at this time was stigmatized is an incredible understatement. Not only that, but it was also very expensive, making it almost impossible for women to obtain a divorce. It was Lucy’s devoted mother, Mrs. Kennedy, who paid for the divorce with the money that her late husband had left her. This inheritance, which was greatly depreciated by the divorce, also paid for a small house in London for Mrs. Kennedy, Lucy and her daughter Esme. Cast out of polite society, Lucy was thrown into haute bohemia, where she decided to make clothes for a living, given that it was the only skill she had that could be potentially profitable. In her mother’s house, she began to make clothing for some friends, and for her sister. In a short five years, she had built a profitable and large business for herself as a couturier and by 1915 Lucy had houses in London, Paris, New York, and Chicago. She remarried in 1900 to Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, but never again would she live under the command of a man. Although Lucy and Cosmo stayed connected personally and through the business of Lucile Ltd, they lived separate lives for most of their marriage.

From the beginning of Lucy’s entrepreneurship she eschewed rules in favour of innovation. In addition to dresses, Lucy began to sell pretty lingerie when women were used to wearing simple white undergarments. The lingerie was displayed in a room called the Rose Room that had a large day bed that was supposed to be an exact replica of Madame Pompadour’s. She named all of her collections and clothes with names like “when passion’s thrall is o’er”, a creative and novel idea that brought life to her clothing. Many also argue that Lucy was the first designer to hold fashion shows in the modern sense, where people are invited to an event to watch models walk down a catwalk to display the clothes. My favourite thing that Lucy did was her insistence on using the same models and giving them goddess-like names, such as ‘Gamela.’ People began to know these models by their names, and came to expect to see them at Lucy’s shows. These models became icons of the Lucile woman. Lucy was also desirous to create fast fashion for the masses: “I’m getting sick of working for the ‘few’ rich people… They don’t like this and that. I am going to work for the millions… I have been no good as a wife and mother and I loathe any idea of ‘society’ or ‘titles.’” While in New York during the war, she twice attempted to create a line of clothing that would suit the masses in that the clothes were affordable and practical. Throughout her career Lucy showed fearlessness, ambition, and an almost complete denial of what an Edwardian woman ‘should’ be.

|

Here is an example of Lucy's intimates being shown and photographed on a real model in a time when people were used to only seeing line drawings of corsets. |

In 1918 her company suffered from her extravagant lifestyle, and was bought out; although she was kept on salary as a director. After a few more attempts to make lavish tea gowns into cheap wholesale clothing, the company went under. Lucy was unable to adapt to the new Jazz Age that was dominated by Chanel and the trend towards more simple clothing. But it is so wonderful that a woman who was able to fully embody the Edwardian ethos through dress was also so modern in many ways.

|

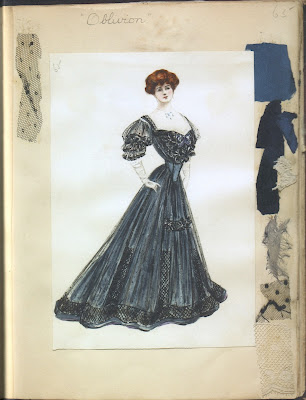

And finally, this is just one of my favourite Lucile Ltd. designs. |

Works Cited

Mendes, Valerie D., and Amy de la Haye. Lucile Ltd: London, Paris, New York and Chicago: 1890s-1930s. London:

V&A Publishing, 2009.

Etherington-Smith, Meredith, and Jeremy Pilcher. The It Girls: Elinor Glyn, Romantic Novelist and Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon,

Lucile, the Couturiere. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1986.

All images have been taken from Valerie D. Mendes and Amy de la Haye's Lucile Ltd.

This woman is fantastic. Good read!!

ReplyDeleteShe was an amazing lady but I was thinking if she lives in this Generation what she'll be wearing? A Black Blank T-Shirt?

ReplyDelete